Sixty years after Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech to an estimated 250,000 people in front of the Lincoln Memorial, civil rights leaders are remembering the man who made that March on Washington possible.

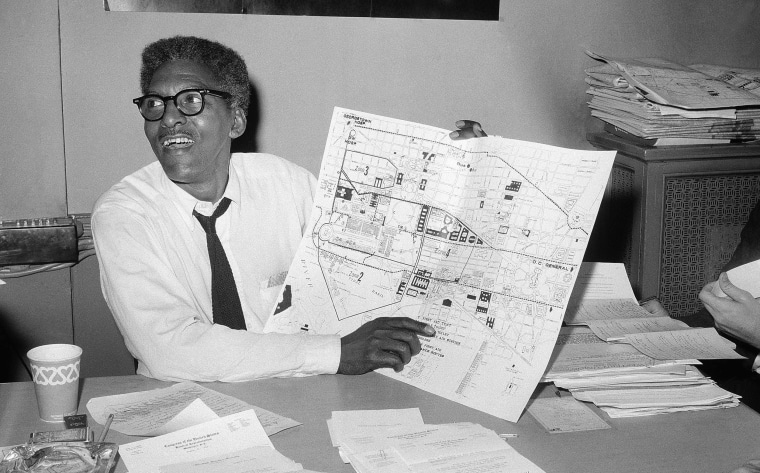

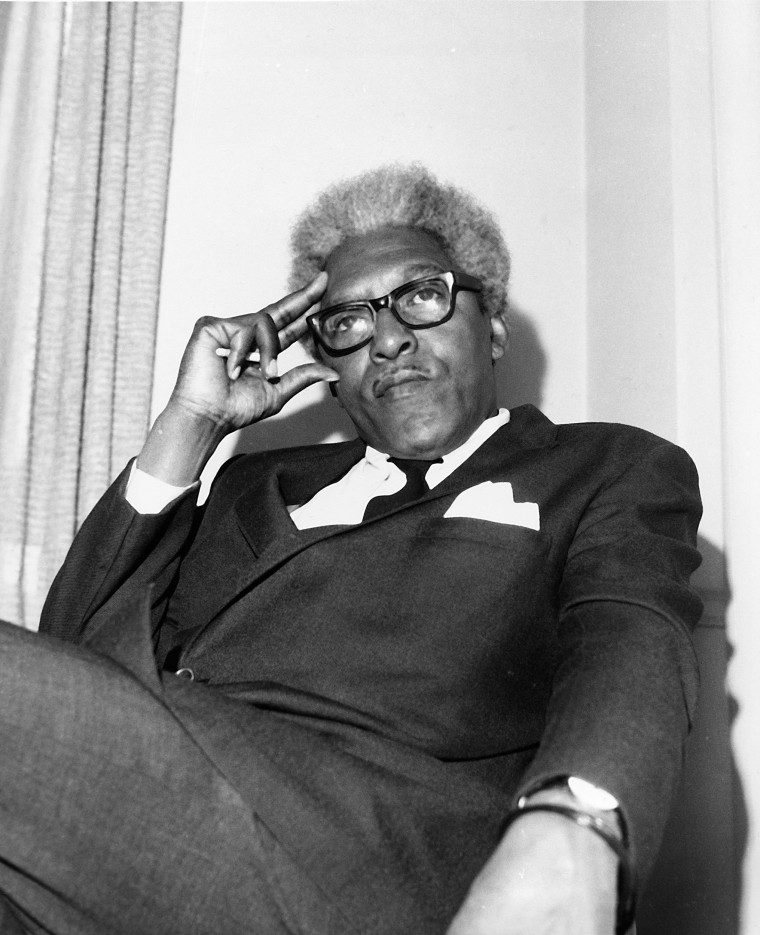

Bayard Rustin was an LGBTQ and civil rights activist best known for being a key adviser to King, and for participating in one of the first Freedom Rides and later planning the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Thousands gathered on the National Mall on Saturday to commemorate the march, two days before its actual anniversary on Monday.

Reflecting on Rustin’s legacy of promoting nonviolent resistance, David Johns, the executive director of the National Black Justice Coalition, a Black LGBTQ civil rights group, said it’s important to acknowledge that there “would not be a March on Washington if it weren’t for a Black gay man whose sexual identity was weaponized against him.”

“If not for him, the fact that he had traveled the globe learning about nonviolent, pacifist movement-making, we would not be here — literally or figuratively,” Johns told NBC News.

Johns said he hopes today’s civil rights activists will be inspired by Rustin to learn “more about pacifist, nonviolent organizing” and “be actively engaged in defending democracy, and otherwise ensure that all Black people can be safe and otherwise thrive.” He also expressed hope that young activists would become “more committed … to understanding [the] Fannie Lou Hamer teaching that, ‘None of us are free unless and until all of us are free.’”

When Rustin died in 1987, at the age of 75, civil rights leader Ralph Abernathy told NBC News that, “Martin Luther King would not have been the person that he was without the aid, the tutorage of Bayard Rustin.”

In a 2020 interview with NBC News, Umi Hsu, director of content strategy at the ONE Archives Foundation, which helps preserve LGBTQ history, said Rustin’s activism is a reminder that queer people of color experience “double the amount of oppressions but also there’s double the power when these politics are addressed.”

“When people have a marginal status in more than one social category, it doesn’t mean that they don’t have any room to participate,” Hsu said. “It’s important to really focus on people who are intersectionally marginalized, because this is where we can see the truths of how oppression systems work.”

Hsu noted that while Rustin was “doing such important work, he actually had a hard time as a gay man. “That put him in a position where he was forced out of civil rights organizing work eventually,” Hsu said.

In 2013, Rustin was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, for his tireless work promoting equal rights.

“For decades, this great leader, often at Dr. King’s side, was denied his rightful place in history, because he was openly gay,” President Barack Obama said during the medal ceremony. “No medal can change that, but today we honor Bayard Rustin’s memory by taking our place in his march toward true equality, no matter who we are or who we love.”

In 2020, California Gov. Gavin Newsom pardoned Rustin for his arrest in 1953 when he was found having sex with two men in a parked car in Pasadena. Rustin served 50 days in Los Angeles County jail and had to register as a sex offender. In pardoning Rustin, Newsom noted how LGBTQ people were unjustly punished for their sexuality by U.S. law enforcement at the time of Rustin’s arrest.

“In California and across the country, many laws have been used as legal tools of oppression, and to stigmatize and punish LGBTQ people and communities and warn others what harm could await them for living authentically,” Newsom said in a statement at the time.

Just last year, Rustin and three other men who were sentenced to work on a North Carolina chain gang after they launched the first of the “freedom rides” in 1947 to challenge Jim Crow laws had their convictions posthumously vacated.

“We failed these men,” said Superior Court Judge Allen Baddour, who presided over the special session. “We failed their cause, and we failed to deliver justice in our community … and for that, I apologize. So we’re doing this today to right a wrong, in public, and on the record.”

For those interested in learning more about Rustin and his legacy, two upcoming projects will be shining a light on the life of the civil rights icon.

A new book about the civil rights leader’s life, “Bayard Rustin: A Legacy of Protest and Politics,” will be released in September. Edited by Michael G. Long, the collection of essays “celebrates the life and legacy” of Rustin, according to its publisher, NYU Press.

And in November, Netflix will release a feature film based on Rustin’s life and his role in organizing the 1963 March on Washington. Titled “Rustin,” the film, which had its trailer dropped Monday, was executive produced by Barack and Michelle Obama.