WASHINGTON — Last Wednesday, three days before a widely feared government shutdown, far-right Rep. Matt Gaetz stood on the steps of the U.S. Capitol and issued a categorical threat.

If House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., relied on Democrats to keep the government open, said Gaetz, R-Fla., there would "very likely" be "a motion to vacate that the speaker would face."

“It’s so obvious I can’t believe I have to say it out loud,” Gaetz told NBC News at the time.

Just hours before the government would run out of money to keep operating, McCarthy decided to defy Gaetz and did just that: He avoided a shutdown by putting forward a bill that Democrats would support.

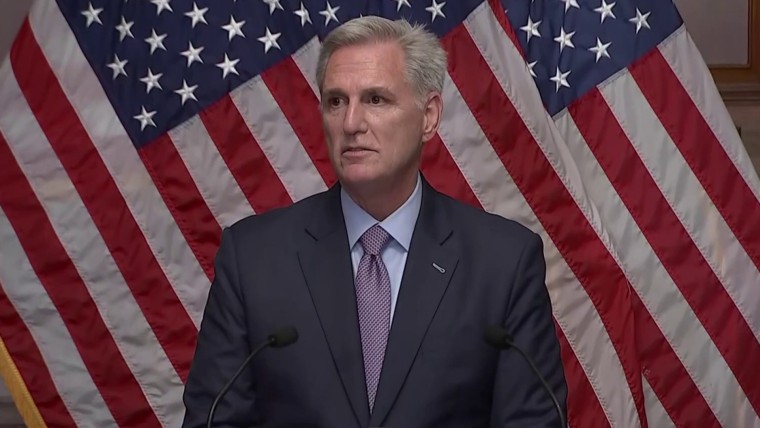

Fast-forward three days. McCarthy is now the first speaker in history to have been voted out of his job — 216 to 210 — with a mere eight Republican detractors in the wafer-thin majority sealing his fate and siding with Democrats to oust him.

“A lot of them I helped get elected, so I probably should have picked somebody else,” McCarthy quipped Tuesday evening of those eight conservative members.

“My fear is the institution fell today,” he said.

McCarthy's 'original sin'

In retrospect, it was the debt ceiling deal in May that was the beginning of the end for McCarthy. It was the first time he did the inevitable and cut a deal with President Joe Biden. He did so on a must-pass bill to avert a global economic meltdown.

Gaetz called it McCarthy’s “original sin.”

While many Republicans were pleased he extracted spending cuts from Biden, hard-liners were furious with what they saw as a mediocre deal and insisted, dubiously, that McCarthy could have gotten more. Gaetz repeatedly proclaimed to McCarthy and his allies that Biden was stealing their “lunch money” — a claim Biden’s re-election campaign embraced and weaponized to tout his negotiating skills.

McCarthy’s allies believe his task was impossible. The debt limit law set up a two-year budget deal with Democrats that McCarthy quickly reneged on. It bought him time with hard-liners, but the moment of reckoning was close. The government had to be funded soon.

In the final days before Tuesday's vote, many Democrats entertained the idea of rescuing McCarthy. They wouldn’t have to explicitly vote for him; they’d just have to vote “present” and lower the threshold of Republican votes he needed to hang on. It was a live ball, according to many Democratic lawmakers and aides at the time, if they got some concessions in return.

But McCarthy faced a conundrum. If he negotiated an arrangement with Democrats, his critics would depict it as a “secret deal” and further diminish his standing on the right. If he rejected that avenue, he might be sealing his fate.

On Tuesday morning, he made up his mind: He was going to survive or fall with GOP votes. He went on CNBC and said “I’m not going to provide anything” to Democrats to get their support.

'One of the most stupid things'

In the run-up to Tuesday’s vote, a handful of moderate House Democrats had received calls from Republican counterparts asking them to vote to save McCarthy’s job, four sources with knowledge of the discussions said. One source described the calls as “begging”; another said they were “temperature-taking.”

Democrats scoffed.

While some initially didn’t like the idea of toppling a speaker for keeping the government open, they couldn’t bring themselves to rescue a Republican who had bowed to former President Donald Trump, launched an impeachment inquiry into Biden despite lacking evidence of wrongdoing, reneged on his budget deal and turned a normally bipartisan defense policy bill into a partisan fight. And their most unifying fear: They simply couldn't trust him.

Inside their closed-door meeting Tuesday, Democrats watched video of McCarthy’s interview Sunday on CBS’s “Face the Nation,” in which he trashed their party as having egged on a shutdown, even though it provided the bulk of votes to keep the government open.

Rep. Gerry Connolly, D-Va., called it “a huge misstep” that clarified the thinking of fence-sitting Democrats.

“One of the most stupid things somebody could do on the eve of your survival vote,” he said.

In the end, every Democrat voted to remove McCarthy.

Last-ditch appeal

Just before the vote, McCarthy’s allies made their last-ditch pleas.

The No. 3 House Republican, Elise Stefanik of New York, said McCarthy had exceeded all expectations in his job.

“Then we definitely need higher expectations,” Gaetz responded.

Rep. Patrick McHenry, R-N.C., said removing McCarthy would only empower Democrats and lead to “more liberal outcomes, not more conservative ones.”

Gaetz was unimpressed.

“It is lovely to hear from the principal architect of Mr. McCarthy’s debt limit deal,” he said. “They took your lunch money.”

Moments later, McCarthy was gone, and McHenry had become the new acting speaker.

The aftermath

Republicans were shell-shocked. Some were solemn and overwhelmed. It was an unprecedented moment in American history for a speaker to be ousted on the House floor, and nobody knew whether McCarthy would make another run at it.

At a conference meeting a couple of hours later, McCarthy broke the news to them: He wouldn’t run for speaker again.

There was no succession plan, and the House would remain paralyzed until a successor was chosen. But who? Who could do a better job than McCarthy?

“Nobody,” a GOP lawmaker texted from inside the meeting.

Other Republicans were surprised by McCarthy’s decision.

“It’s unexpected. … I thought he would” run again, said Rep. Ralph Norman, R-S.C., an original McCarthy foe who voted to keep him in the speaker’s job Tuesday. “I think he just is dejected. He’s tired. And he’s a good man.”

McCarthy told reporters that he “might” endorse a successor, but he didn’t say whom. He said his advice to that person would be: “Change the rules” of the House so it couldn’t be held hostage by Gaetz or anyone else under the one-person motion-to-vacate rule.

Across the Capitol, senators were taking in the news.

“The House is in chaos,” Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., said in an interview.

“There’s probably a reason this has never happened in the history of the country,” he said. “We’ve been around for 200-some years. Everybody before us thought this wasn’t a good idea. I think, when it’s all said and done, people will look back and say: That’s not a good idea. But it is what it is.”

Seconds later, Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., walked up to Graham and joked: “Hey Lindsey, you know you don’t have to be a member of the House to be chosen speaker.”

“Yeah, but you've got to be sane,” Graham replied.

Both of them chuckled.

“And I’m sane enough to say no,” Graham added.