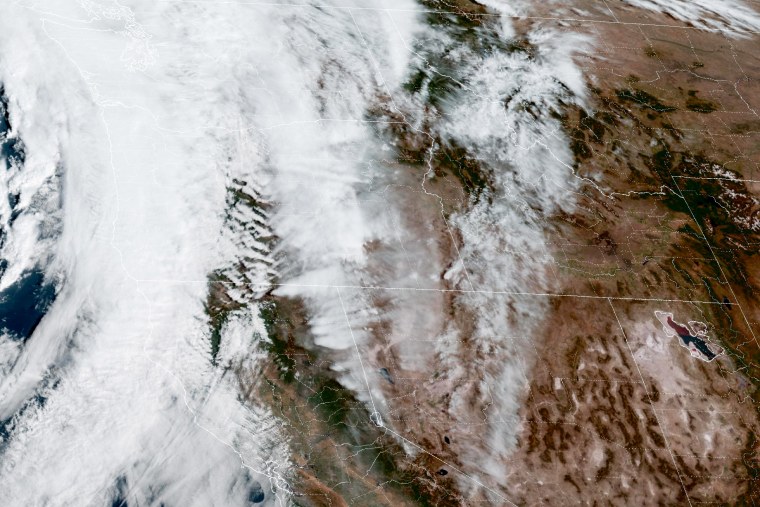

An atmospheric river storm barreled into the Pacific Northwest on Sunday, bringing several days of heavy rain, most likely ending the wildfire season in many areas and offering a bit of a reprieve for a region suffering from extreme drought.

In the Seattle area, nearly an inch of rain fell in 24 hours, said Dev McMillian, a National Weather Service meteorologist. The rain comes just days after the city’s utility asked 1.5 million customers to conserve water as its supply dwindled because of a regionwide drought.

Flash flooding is possible near the Oregon-California border, according to a forecast from the Center for Western Water and Extremes at the Scripps Institute for Oceanography. Because the drought in the Pacific Northwest is so severe, the center is not forecasting any river flooding.

More than 43% of Washington has been in “severe drought” or worse, according to the U.S. drought monitor. In Oregon, 27% of the state qualified for that category.

Several days of soaking rain should put the wildfire season to bed in the western parts of both states, said Matthew Dehr, a meteorologist for the Washington Department of Natural Resources’ fire management division.

“It’s a pretty big sense of relief,” Dehr said. “This is going to put to rest the chances of any large timber fires in Washington, the ones that cause our big smoke events.”

In August, several wildfires near Spokane took off in extremely dry and windy conditions, killing two people and burning down hundreds of homes.

Dehr said a tragic wildfire season could have been far worse. Fire danger ratings in parts of the North Cascades and Olympic mountain ranges reached their highest levels in recorded history because the landscape was so parched.

“It was a powder keg ready to go, really, and we just got lucky,” Dehr said, adding that there were relatively few lightning strikes to spark fires this year.

Dehr said that grass fires could be possible in the inland Northwest in October but that the risk has been greatly diminished by this storm.

The rainfall should help alleviate the drought, Dehr said, but forecasters remain concerned, particularly as an El Niño winter approaches. The El Niño pattern, which is associated with dry winters in the Pacific Northwest, has contributed to meager snowpacks in the past.

Atmospheric rivers are plumes of moisture that originate in the tropics. They often stretch thousands of miles across the Pacific Ocean and can drive patterns of extreme weather in California, Oregon and Washington.

Climate change aggravates such storms’ impact because a warmer atmosphere can hold and transport more water vapor. Last winter, California was battered by a series of more than a dozen atmospheric river storms, which caused landslides and extreme flooding.

The Center for Western Water and Extremes, which tracks atmospheric rivers closely, forecast the series of storms as a Category 4 storm. Category 4 storms are considered extreme, and they are expected to create hazardous conditions, with a chance of positive effects for the water supply.