The state of Texas has swept into the Houston school district, seized control of some 85 schools, most of which are majority Latino or Black, homogenized teaching and curriculums, remade some schools' libraries into discipline and study centers, and removed or reassigned teachers and librarians.

The state has said it's had to make the abrupt and aggressive intrusion to rescue the schoolchildren in the district — whose student population is 62% Latino and 22% Black — from years of education failure that year after year leaves many illiterate or lagging their peers in math.

But the stripping away of pieces of already underresourced Latino and Black public schools in the district, even some that had been earning high performance marks, conjures the not-too-distant practices of separate and unequal education, if it was available at all, for Latino and Black children in the state.

“The problems that created educational inequities can’t be solved by one element,” said Thomas Saenz, president and general counsel of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, or MALDEF.

“You need comprehensive attention, resources, monitoring. To turn around a school, much less a district," he said, "that takes resources and that’s the real problem. These overwhelmingly Black and brown districts are starved of resources.”

As in other parts of the country, Texas from its beginning prohibited Black children by law from education. A constitutional amendment required separate schools for "the white and colored children" that was also applied to Mexican American children, as civil rights attorney Al Kauffman of San Antonio wrote in a law journal article.

The state packed Mexican American children into inferior "Mexican schools" where books and facilities were inadequate, few grade levels were taught and children were assumed to be destined for farm and domestic work.

The schools were created under the guise of providing English language instruction, but instead became state repositories for children who had Spanish last names, whether they knew English or not. When Mexican schools were abolished, Mexican American and white children were taught in separated classrooms in some parts of the state, Kauffman wrote.

'No reason' for inequities within the district

Saenz said that while the takeover and subsequent changes in certain Houston schools are not a separate and unequal scenario, conversion of some of the schools' libraries and removal of their librarians and some of the other changes have created a situation that is “certainly inequitable” and “probably unlawful."

“There’s no reason for Houston school district to have such a significant deviation between schools,” Saenz said. Such inequities happen all the time, but are usually among school districts, not within them, he said.

"A school district that has one budget, one governing body, one superintendent, should ensure that every school at a particular level, every high school, every middle school, every elementary school has the same services, the same access and that's what this does not provide," Saenz said.

Because of Houston’s predominantly minority status, there are Latino and Black children in schools that are not subject to the recent drastic changes. However, almost 40% of Texas students attend predominantly nonwhite, high-poverty school districts.

Mexican Americans in Texas have endured an almost 200-year struggle for equal education that has been waged with court cases, protests, walkouts, boycotts and creation of their own schools. One of the first lawsuits filed by Mexican Americans in Texas over unequal education was in 1930 in Del Rio.

“We were fighting these issues in the 1950s and 60s and 70s and 1990s and 2000s. How you can you say education is the great equalizer when it remains unequal? And it’s not by accident. It’s on purpose,” said David Hinojosa, director of the Educational Opportunities Project at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, a racial justice legal group.

According to Kauffman, the state institutionalized segregated schools through school choice plans, gerrymandered districts, transfer policies, neighborhood schools, racist public infrastructure placement, and housing regulation and zoning plans. And the state’s fundamentally unfair school finance system based on property wealth is playing a role in keeping them inequitable. Many of the schools Houston has targeted are in property poor communities.

Those systemic inequities are compounded by “arbitrary accountability systems” premised mostly on standardized tests that tend to have biased impact on students of color and low-income students, said Hinojosa, whose litigation portfolio includes landmark cases on desegregation and the state school finance system.

“The collision course between segregating students and underfunding the education of students of color is not by accident,” Hinojosa said. “And trying to fix this by closing libraries and taking over schools from communities of color is merely going to perpetuate unequal opportunity.”

'Feels like a direct attack'

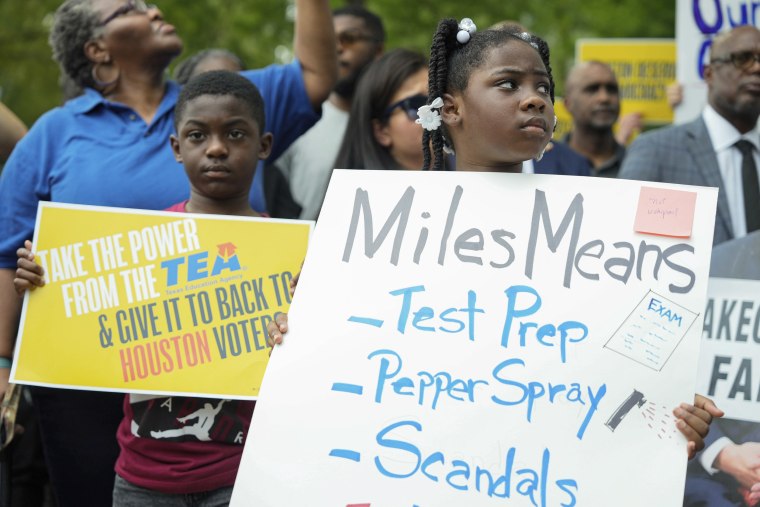

Jessica Campos, 41, has three children in Houston’s schools. One attends Pugh Elementary, one of the initial 28 schools that have seen drastic changes since the state took over the district and imposed what the state-appointed superintendent, Mike Miles, calls the New Education System model.

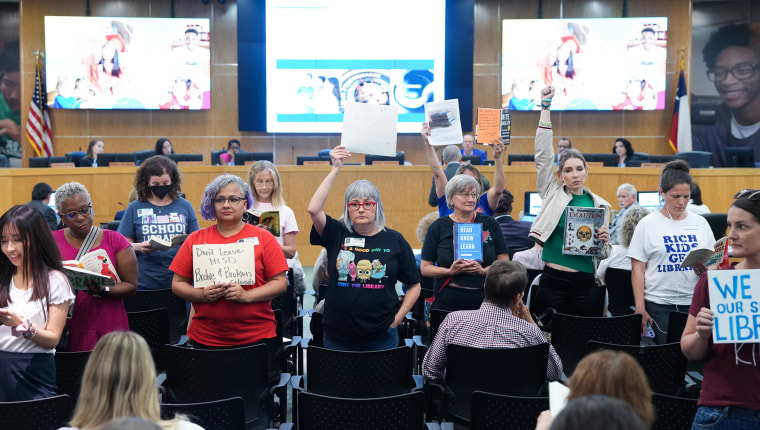

In schools where the state has taken control, teachers are being told to conform to a new, rigid curriculum and instruction methods, or be replaced. In some schools, librarians have been removed and the libraries have been turned into spaces where disruptive students are sent to attend their classes via video conferencing and where students who do well on daily quizzes are sent to do extra work provided in packets on their own or in groups.

Under that model, Pugh Elementary’s library was one of those converted and no longer has a librarian.

The library was an important part of education for Campos' daughter because she has a learning disability and her independent instruction happened in the library. The child was behind her peers until the end of this past school year and for the first time did not have to attend summer school to catch up, she said.

Campos has been disturbed by the instruction method that does not allow teachers to repeat material during the presentation for children who can’t keep up and requires sending those who can pass a quiz on the material to the converted library to work on their own.

“Children are being separated and divided, you know, the smart ones and the kids that don’t get it, and that’s causing a lot of emotional trauma,” said Campos, who has become an active opponent of the changes as a member of Community Voices for Public Education since the takeover began in the summer.

The forced overhaul “feels like a direct attack” on the Hispanic and Black communities, she said. She has taken it upon herself to translate materials for parents who are not proficient in English and holding parent meetings at a local restaurant.

"I feel like I have let my child down because I’m broke and I can’t pull her out of this neighborhood. And I am not the only mom who feels this way," Campos said.

Mayra Lemus, 35, began organizing protests when the changes reached Cage Elementary, the public school where her gifted and talented son is a fifth grader.

She said she can’t understand why the principal at Cage decided to adopt the New Education System when it was not a failing school. It had an A rating in the 2021-22 school year and almost half of its 440 students were in bilingual education that year.

Her son's teacher was reassigned his first week of school and the replacement hadn’t taught for 20 years, she said. Then that teacher was replaced. Her son, she said, is bored by the scripted curriculum and the lifelessness of the school. Its library is among the converted ones.

“My thing is, why not focus on the school that was having the issue?” Lemus said. "Why take everybody with you?”

Defending changes, aiming to 'correct' inequities

The Houston Independent School District, or HISD, takeover was triggered by a 2015 law, crafted by a Black Democratic lawmaker, Rep. Harold Dutton Jr., from Houston after two of the district’s high schools failed repeatedly to score beyond a C in state academic evaluations. He has stood by the law as criticism has risen against the takeover, saying elected boards repeatedly failed to sufficiently improve the academic performance of two high schools.

Orlando Reddick, division superintendent for north HISD, told NBC News that the New Education System model that Miles developed — is “wholescale system reform” that “maximizes” the time and resources that schools have to support children’s learning.

“The role that we’re, that I’m here and my colleagues are here to support, is what can we do to get the high quality instruction to you best results for a family?” Reddick said.

“Maybe we have made mistakes in the past and I can’t speak to the past of the district beyond when I was here 10 years ago for that short period of time or previously, but if there were inequities, that’s what we have to correct and self-correct right now, and that’s that the additional resources go into schools that were underperforming,” he said.

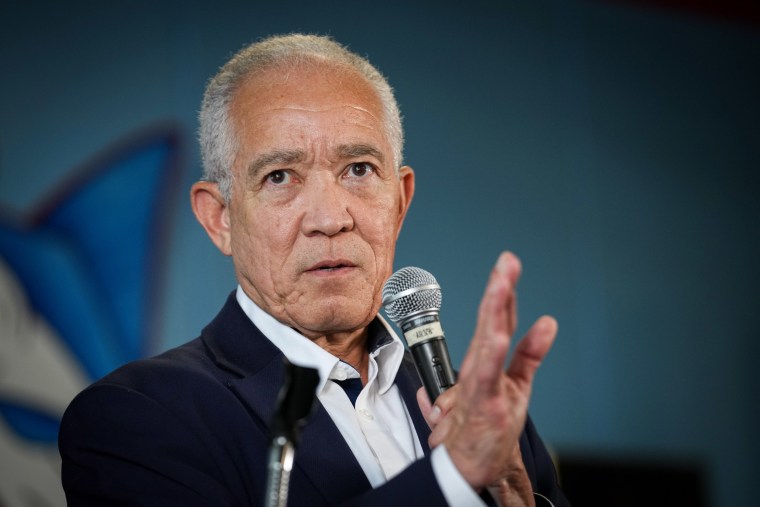

Miles, a West Point graduate, was CEO and founder of Third Future charter schools, whose regimented education style he's repeating at HISD and has been used at a few other Texas schools. He has championed what he calls wholescale change by starting with a few schools and using them as "proof points" to expand to other schools.

The model uses the first 45 minutes for a lesson, followed by a five-question quiz that allows teachers to determine the students who need to stay behind for more instruction and those who will advance to the converted libraries dubbed “team centers” to do advanced work. Librarians in some of those schools were replaced with “learning coaches.”

“The model has where it infuses more staff into the classroom to support the student so that we can get to an ability for the student to read” or reach math literacy, Reddick said.

The new system provides higher salaries for teachers and more support staff.

In an appearance at the Texas Tribune Festival in Austin, Miles set a four- to five-year-deadline for his New Education System to show results, but also said: “If we don’t start to see the needle move in two years, you should fire me.”

The forced changes in the Houston public schools come as Texas Gov. Greg Abbott has been promoting “parental rights” in children’s education for those who oppose books and materials dealing with LGBTQ individuals and teaching about systemic racism.

He has called an Oct. 9 special legislative session on school choice and education funding. He has been pressing lawmakers for months to allow public funds to be used for school vouchers for private or parochial schools. Attempts to get such legislation in previous sessions failed.

But in Texas, school vouchers were once approved by the state House as a way for white parents to pull their children out of schools being integrated.

In Houston, Campos didn't feel like she had a say when it comes to her child's school.

“I feel like I want to scream at the top of my lungs and maybe someone will hear us,” she said, her voice beginning to fill with emotion. “It feels like I can’t do anything."